Iran and Global Trade: Lessons from the 17th Century

With the prospect of a nuclear agreement and the lifting of sanctions, Iran has become the hottest about-to-emerge market for investors and business leaders. But the anticipated gold rush of major multinational corporations entering the Iranian market is far from new. In fact, Iran’s history of engagement with Western corporations dates back to the 16th and 17th centuries and the reign of the Safavid Shahs, particularly Shah Abbas.

The history of this first “commercial revolution” contains three important lessons for investors and business leaders eyeing Iran today.

Intense competition means no guarantees.

The first Western corporations to do business in Iran date back to the 17th century, when the English East India Company (EIC) and the Dutch Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) integrated Iran into their global trading networks.

But before the English and Dutch built their merchant empires, it was the un-corporatized Portuguese merchants who first brought high-volume maritime trade to Iran and the Indian Ocean region, controlling the strategic ports of Hormuz in Iran, Goa in India, and Malacca in Malaysia.

Fierce competition dictated access to the Iranian market in this period. In fact, although Portuguese traders had an effective monopoly in the 16th century, the coordinated efforts of the EIC and VOC would destroy the Portuguese trading networks. Some decades later, in the early 17th century, merchants from the EIC and VOC began competing directly, and despite the initial advantage of the EIC, which enjoyed a privileged relationship with the royal court, the VOC would wrest control of Persian Gulf trade for the next century.

It is taken for granted that those companies with a presence in Iran today will be best positioned in the post-sanctions period. But as demonstrated by the rise and fall of the Portuguese, the English, and the eventually the Dutch, there are no guarantees when competition intensifies.

A pertinent example that my colleague Daniel Rad discussed in this blog on Monday is the French car manufacturer Peugeot. Despite a decades-long presence in Iran and a dominant market share, increased competition from Chinese and Korean manufacturers such as Kia, Hyundai, and Chery, has been chipping away at Peugeot’s position.

Just as Portuguese traders lost their stronghold on the Iranian market in the 17th century, the current multinational market leaders could lose their privileged positions as more companies eye Iran’s strategic market.

Connective infrastructure is of paramount importance.

The competition between the Portuguese, the EIC, and the VOC at the end of the 16th century was all about establishing global trade networks. By controlling strategic ports, goods could travel more quickly and reliably from sites of cultivation or production in the Far East and to markets for consumption in the Near East and West. More efficiency meant higher profit margins for the companies financing each voyage.

It was through the competition for these strategic ports that Iran gained a key component of its current geostrategic position—access to the Persian Gulf.

Around the time the Portuguese arrived at Hormuz, Safavid rulers had only a tenuous hold on the Southern coast of Iran. The Portuguese faced no real resistance when establishing their port, and even constructed a fortress to protect their position.

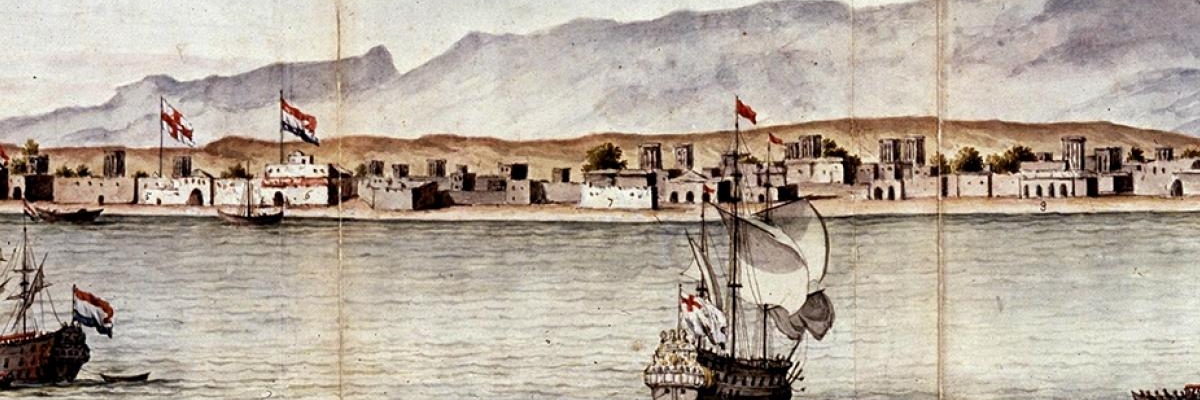

The establishment of the first directly Iranian port cities was spurred by the rise of global trade routes in the 16th century. Bandar Abbas, was founded by the Safavid ruler Shah Abbas with cooperation from both the EIC and VOC. British and Dutch forces provided the critical firepower for Persian troops to take the Portuguese fort at Hormuz and claim control over the coastline. Today, Iran has several major ports or bandaran, including Bandar Imam Khomeini, Bandar Abbas, and Chabahar.

In this way, competition over international trade spurred the Iranian state to make a greater effort to connect the country to the world.

Aside from the development of seaports (which will certainly accelerate in a post-sanctions environment— the expansion of Chabahar a particularly ambitious project) the development of Iran’s airports might provide the best modern parallel.

Airport expansion is commonly attributed to rising tourist traffic and growth in Iran’s tourism industry is to be expected. But, the recent rise in the number of business travelers and the expanded need for cargo facilities and logistics infrastructure will be the greatest drivers of airport development.

Even now, at Tehran’s Imam Khomeni International Airport, the best facilities are reserved for “Commercially Important Persons” or CIPs, who have the privilege of travelling through the newest and most modern terminal. The airport’s ambitious $2.8 billion dollar expansion plan is designed to bring the overall standard of facilities in line with those on offer at the dedicated CIP terminal.

The scholar Willem Floor, an expert on Persian Gulf trade, relays the role once played by Bandar Abbas: “In 1628 [the English traveler] Thomas Herbert confirmed the lively, cosmopolitan nature of the new port, where he reports seeing English, Dutch, Danish, Portuguese, Armenian, Georgian, Muscovite, Turkish, Arab, Indian, and Jewish merchants.”

Without the right infrastructure, Iran will struggle to attract a similarly cosmopolitan mixture of international business travellers for the 21st century. New connective infrastructure will be key.

Domestic consumption will drive growth.

When thinking about Safavid Iran’s economy in historical terms, there is a tendency to assume Iran, midway between Europe and the Far East on the famed Silk Road, was just a way station for ships and caravans passing through.

But the Safavid Empire was large and powerful, and competed for regional influence with the Ottomans in the West and the Mughals in the East. As with any empire of its size, the Safavid dynasty had an elaborate court culture, which reached its height of opulence at the time of Shah Abbas.

In this light, Shah Abbas’ cooperation with the English and Dutch merchant corporations enabled Iran itself to emerge as a consumer marketplace. Given the ousting of the Portuguese with the help of the British and French, and victories over Ottoman invaders, “the consolidation of Safavid imperial power” called for an “an enhanced culture of courtly display and consumption of luxury goods” according to a study by historians Derek Bryne, Kevin O’Gorman and Ian Baxter.

With this new courtly display, the upper classes outside the confines of the court began to emulate the new consumerist behaviors. As Rudi Matthee has argued, “Not only was Safavid Iran being incorporated into a new global matrix of commerce and consumption; Iranians played an active role in its very formation by enthusiastically embracing the new consumables and adapting them to their needs and tastes.”

The 17th century commercial revolution that brought varied commodities like “spices, textiles, tin, camphor, Japanese copper, powdered and lump sugar, zinc, indigo, sappanwood, chinaroot, gum lac, benzoin, iron, steel, and sandalwood” to Iran, helped establish the consumerist attitudes seen among Iranians today.

The Safavid ruler and his royal court were the key “early adopters.” As Byrne, O’Gorman, and Baxter have shown, “by working to overcome… cultural inhibitions among the wealthy” the royal court “established a behavioral model, a propensity to consume, that other social strata could later emulate.”

Today, the consumer appetite for foreign goods can be seen in, for example, the increased popularity of shopping malls in Iran. Once confined to small shopping arcades in the wealthier enclaves of northern Tehran, major mall development projects have sprung-up that cater squarely to Iran’s middle class. The kind of aspirational consumerism that only a Western-style mall can provide, through which the middle class can emulate the tastes of the upper class, directly reflects the ways in which the 17th century aristocracy emulated the Shah and his court.

It is likely that Iran’s post-sanctions moment will be characterized by the increased consumption of accessible luxuries. To be clear, items such as smartphones, home appliances, quality cosmetics, the latest fashions, or imported foods have been widely available in Iran. But increased competition for market share by multinational corporations will drive down prices and increase inventories in the country as these corporations cut out middlemen and invest directly into retail opportunities in Iran.

Most importantly, access to these goods will be expanded beyond the major cities of Tehran, Mashhad, Tabriz, Esfahan and Shiraz as supply chains develop. Iran’s middle and lower class consumers will benefit as their purchasing power is stretched further in malls and hypermarkets around the country.

Should the Iranian consumer be unleashed, the domestic purchasing of everyday luxuries will have a significant impact on Iran’s economic growth in an echo of trends from centuries earlier.

The legacy of EIC and VOC are historical evidence of how Western corporations can deeply shape the Iranian marketplace. Investors and business leaders, in looking to history, should come to recognize that they can potentially wield a similar capacity to shape Iran’s post-sanctions future. Whether it is building new infrastructure or influencing consumer culture, the responsibility will be profound.

Photo Credit: Archeonaut